A cache of donated baby teeth -- leftovers from a famous radiation exposure study from the 1950s -- that had been hidden away in an old ammunition bunker at a university until about 20 years ago will now be used to study cognitive decline in older age.

Teeth from the Baby Tooth Survey in St. Louis will be used to study how early exposure to heavy metals may be linked to neurodegeneration. The study is being led by Marc Weisskopf, PhD, of Harvard University's T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

There is a lot of research interest in the idea that early life exposures can have an effect on health much later in life, and this theory has been suggested in animal studies, he said.

"But in humans, this is typically an extremely tough research area to work on because of the difficulty in getting accurate exposure information from some 60-70 years earlier. These teeth make this possible," Weisskopf said.

Teeth with a past

The approximately 100,000 teeth that were left over from the Baby Tooth Survey were found in a closet in an ammunition bunker at Washington University in St. Louis in 2001. The survey helped change history and likely saved numerous lives.

Marc Weisskopf, PhD, of Harvard University's T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Marc Weisskopf, PhD, of Harvard University's T.H. Chan School of Public Health.In 1956, the U.S. Public Health Service issued a report suggesting that the St. Louis area was a hotbed for radioactivity due to above-ground nuclear weapon testing during the early years of the Cold War. This alarmed the community, leading faculty members at Washington University, including Edward Condon, former Manhattan Project physicist, and Barry Commoner, the Citizens Party candidate for the U.S. presidential race in 1980, to create the Commission of Nuclear Information.

In 1958, the committee created the Baby Tooth Survey following earlier evidence that showed the isotope strontium-90, which is a byproduct of nuclear fallout, followed the typical pathways of calcium collected in cow's milk, which children drank while their baby teeth were developing.

Researchers collected hundreds of thousands of baby teeth from children born in the 1950s and 1960s and measured the teeth for exposure to radiation. The organization's research revealed that children born in 1963 had 50 times more strontium-90 in their teeth than those born in 1950, which is before most atomic bomb testing occurred. The study accelerated passage of the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, which banned nuclear testing anywhere except underground. It was signed in Moscow in August 1963 by President John F. Kennedy and leaders from the U.K. and the Soviet Union.

The discovery

Finding the teeth, as well as donor information cards, at the university was a major discovery and surprise. The St. Louis study required teeth to be crushed into powder to test for strontium-90, so it was assumed that they were gone. It is unclear how long the teeth had been locked away; it's possible they had been there since 1970, when the survey ended.

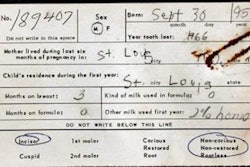

A baby tooth donated to the Baby Tooth Survey in St. Louis and the donor's information card. All images courtesy of Weisskopf.

A baby tooth donated to the Baby Tooth Survey in St. Louis and the donor's information card. All images courtesy of Weisskopf."I don't know the history of how the teeth got stored away and forgotten, but that seems to be what happened," Weisskopf said.

The university donated the teeth to the organization Radiation and Public Health Project, which was conducting a study of in-body radioactivity near nuclear plants. About 80% of the teeth are from people born in the St. Louis area. The rest are from those born in each of the 50 U.S. states, plus 45 foreign countries, Joseph Mangano, executive director of the radiation project, said in an organization press release.

"This is one of the largest known collections of human samples," Mangano said.

A few years ago, Weisskopf learned that Mangano had the teeth, they connected, and then he applied for funding. In 2020, Harvard received a five-year, approximately $6 million grant from the Superfund Research Program of the U.S. National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences to establish the Metals and Metal Mixtures: Cognitive Aging, Remediation and Exposure Sources (MEMCARE) Superfund Research Center.

About two dozen researchers will study how exposure to hazardous substances, such as industrial solvents, and heavy metals, including lead, mercury, and arsenic, affects cognitive aging. They are basing this study on what has been discovered in animal research.

"Animal work on early-life lead exposure and Alzheimer's-like pathology in late life has suggested that epigenetic modification -- marks on the DNA that change the readout of the DNA rather than the actual sequence of the DNA -- may play a role," Weisskopf said.

Additionally, they will study how to protect the public from these metals and substances that are found in contaminated water, soil, and air at hazardous waste sites throughout the U.S.

Locating donors

Weisskopf's research will require finding 1,000 adults who participated in the St. Louis study. The researchers have managed to locate current addresses for about half of the people they have attempted to find. A letter was sent to each person, which resulted in about 30% participation. Weisskopf is pleased with the response, considering the only data they have are basic demographic information that was given when the teeth were donated.

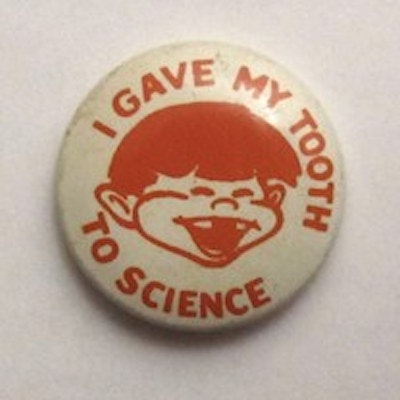

Buttons were given to children who donated their teeth.

Buttons were given to children who donated their teeth."Most of the feedback we have gotten suggests folks have been extremely excited to participate again," Weisskopf said. "They remember their prior participation quite fondly."

In the beginning, the participants will be asked to do an online questionnaire about many aspects of their life and do online cognitive testing.

"We are hoping to recontact them every few years and continue to monitor all aspects of their health," Weisskopf added.

Other opportunities

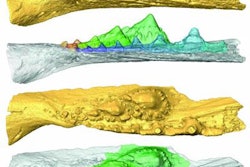

When it comes to using the teeth for other research, the possibilities may be endless. The teeth could be used to study genetics, dentistry, anthropology, and more, Mangano said.

"Combined with the data we collect on their current health, the teeth can be used for all sorts of research on early life factors and later life health," Weisskopf said. "Whatever we can determine from the teeth, we can do research on."