Sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption is declining, according to a new study from Harvard University researchers. While Americans are drinking fewer sugary beverages than they were a decade ago, consumption still exceeds the limit recommended by the U.S. government.

Americans appear to be getting the message about the dangers of added sugars, according to new research from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. However, sugary drink consumption has not declined evenly among all race and ethnic groups in the U.S.

"[Sugar-sweetened beverages] are a leading source of added sugar to the diet for adults and children in the U.S., and their consumption is strongly linked to obesity," stated lead study author Sara Bleich, PhD, in a press release accompanying the research. "Understanding which groups are most likely to consume SSBs is critical for the development of effective approaches to reduce SSB consumption."

Bleich is a professor a of public health policy at Harvard. The study was published in the journal Obesity (November 14, 2017).

Sugary drink consumption varies by population

In addition to causing dental caries and erosion, frequent consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages is linked to obesity, high blood pressure, and type 2 diabetes. Public health advocates and researchers have encouraged Americans to reduce their sugary drink consumption, and some U.S. cities have started taxing sugar-sweetened beverages.

To see if the message is reaching the general public, Bleich and colleagues looked at data from the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) from 2003 to 2014. The surveys are conducted by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and are designed to provide nationally representative data about the health status of children and adults in the U.S.

The researchers' final analysis included 18,600 children between the ages of 2 and 19 and 27,652 adults age 20 and older. All participants were interviewed by NHANES researchers about their overall beverage consumption within the past 24 hours. Bleich and colleagues then analyzed their results over time.

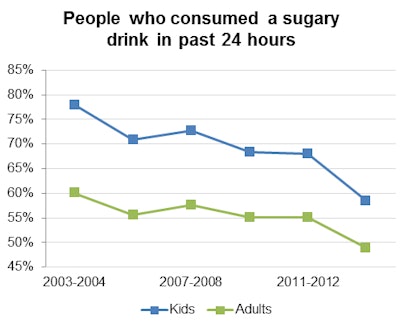

Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption declined significantly between the 2003-2004 survey and 2013-2014 survey for both children and adults. The number of calories consumed from sugary drinks also declined, while water consumption rose.

"The overall decline in both beverage and SSB consumption is consistent with previous literature, suggesting a recent 'turning point' toward lower energy intake in the U.S. diet," the authors wrote. They added that the decline may be attributed to "widespread discussion and media coverage of the role of certain foods in promoting obesity, changes to food allowances, ... improvements to school feeding programs, and product reformulations by food manufacturers and retailers."

While sugary drink consumption declined significantly overall, it did not decline for Mexican-American and non-Mexican Hispanic adolescents or for most non-Hispanic black adults. These groups also have a higher risk for obesity and diabetes, Bleich and colleagues noted.

"Although our results suggested that SSB consumption is declining overall, they also highlighted the need for reducing disparities in SSB consumption by race and ethnicity," they wrote. "Current public health efforts may be helpful for narrowing this gap."

The study authors also cautioned that sugary drink consumption is still high, with some demographics consuming more than recommended by public health organizations.

"Overall, beverage consumption declined for children and adults from 2003 to 2014, driven primarily by a decrease in the percentage of SSB drinkers and lower per capita consumption of SSBs," they concluded. "However, adolescents and young adults still consume more than the recommended among of SSBs set by the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, and levels of SSB consumption are persistently highest among black, Mexican-American, and non-Mexican Hispanic individuals, who are also at higher risk for obesity."