Researchers from the University of Washington (UW) School of Dentistry were awarded a $2.7 million grant from the U.S. National Institutes of Health to explore how and why people react differently to dental plaque accumulation, according to a news article published on the university's website.

A group that includes microbiologists, immunologists, and periodontists will explore three types of gum inflammation, or gingivitis. Periodontitis, if it is not treated, degrades gum tissue and the bone that supports teeth. Periodontitis has been linked to heart disease.

Investigators, led by microbiologist Jeffrey McLean, PhD, will track mechanisms that control gum inflammation, seeking to identify bacteria, fungi, viruses, and metabolites associated with three types of responses to dental plaque accumulation occurring at and below the gumline.

The first response type comprises individuals who respond to dental plaque with strong, swift inflammation. The second response type consists of people who trend toward a more moderate inflammatory response, and the third response type includes people who have a slow response to dental plaque.

We think eventually, knowing someone's responder type could also relate to their response to other things," McLean said in a UW News article. "Even, potentially, the virus that causes COVID. If you’re a certain type of responder, you might have that response to other viral infections, too."

Participants in the study will undergo a full dental cleaning and stop brushing some of their teeth for three weeks. As plaque builds up and inflammation occurs, the investigators will take samples from participants' mouths. After the three-week period is over, participants will receive another deep cleaning, which will abate the inflammation.

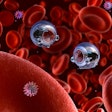

Researchers will collect a sample of oral bacteria from study participants.Image courtesy of Dr. Shatha Bamashmous.

Researchers will collect a sample of oral bacteria from study participants.Image courtesy of Dr. Shatha Bamashmous.

Understanding which response a patient has to dental plaque could help dentists tailor treatments and products specifically for their patients, the university said.

"These discoveries [could] open a path to develop treatments and products specifically designed for different response types -- for example, a toothpaste that replicates the bacterial conditions found in slow responders’ mouths could help strong responders stave off gingivitis," according to the UW News article.

The award includes collaboration with the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio.