Higher numbers of deep and lobar cerebral microbleeds were found in stroke patients who had Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) that were positive for the collagen-binding protein Cnm in their mouths. The study was published on January 27 in the European Journal of Neurology.

Cnm-positive S. mutans induce cerebrovascular inflammation, impair the blood-brain barrier, and cause brain bleeding, wrote the authors, who are from Japan, the U.K., and the U.S. Since cerebral microbleeds affect the long-term prognosis of stroke patients, reducing the bacteria in the oral cavity may serve as a new treatment for stroke patients.

"Cnm-positive S. mutans was significantly related to the presence of >10 CMBs (cerebral microbleeds), a predictor of future ICH (intracranial hemorrhage), ischemic stroke, and mortality," wrote the authors, led by Dr. Satoshi Saito, PhD, of the National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center in Suita, Japan.

Approximately 90% of the general population has S. mutans in their oral cavity. The pathogen, which lives in dental plaque, is best known for causing tooth decay. Dental bacteria, including Cnm-positive S. mutans, cause infective endocarditis. Microbleeds in the brain precede intracerebral hemorrhage in infective endocarditis, according to the study.

Previously, the authors published literature citing a connection between S. mutans that express Cnm and an increased risk of deep cerebral microbleeds. Also, aggravated bleeding occurred in the cortical and deep gray brain matter of stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats when they were administered Cnm-positive S. mutans intravenously, according to research. However, how Cnm-positive S. mutans contribute to microbleeds in the lobar area of humans' brains remains unclear.

To further explore the association between these bacterial pathogens and cerebral microbleeds, the authors conducted a retrospective study of 428 stroke patients who had undergone oral bacterial exams. Of the patients, 326 patients (76%) had S. mutans and 102 patients (24%) did not have the pathogen in their oral cavities (24%). In the group in which S. mutans were detected, 72 patients harbored Cnm-positive S. mutans and 254 had Cnm-negative S. mutans. However, four of the Cnm-negative patients were excluded because they had not undergone magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

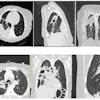

Cerebral microbleeds were detected on T2-weighted MRIs. Deep microbleeds were defined as hypointensities located in the deep gray matter of the basal ganglia or thalamus or the white matter of the corpus callosum or internal, external, or extreme capsule. Microbleeds in the lobar were defined as those in the cortical gray or subcortical white matter, according to the study's authors.

Harboring Cnm-positive S. mutans was associated independently with the presence of more than 10 microbleeds in the brain (adjusted odds ratio, 2.20). After adjusting for age, sex, hypertension, stroke type, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy, there were higher numbers of deep (adjusted risk ratio, 1.61) and lobar (adjusted risk ratio, 5.14) cerebral microbleeds, respectively, the authors wrote.

Nevertheless, there were several limitations of the study, including outcome data that were not collected, because the study was done retrospectively. The researchers are performing a prospective multicenter observational study to evaluate the effects of Cnm-positive S. mutans, they wrote.

"In conclusion, we found that Cnm-positive S. mutans was associated with a higher number of both lobar and deep CMBs (cerebral microbleeds)," Saito et al wrote.