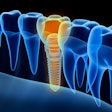

The efficacy, safety, and efficiency of the placement of dental implants immediately after an extraction is well-established in dentistry. However, it is entirely possible, even likely, that the tooth to be extracted has periapical lesions. In those situations, how safe is it to proceed?

Researchers from the dental schools at the University of Seville and Complutense University of Madrid in Spain, as well as the Cardiff University School of Dentistry in the U.K., sought to answer that question in a three-year prospective study published in the Journal of Dentistry (May 2014, Vol. 42:5, pp. 645-652). Their conclusions should be comforting to clinicians who place implants.

"Immediate implant placement can be considered a safe, effective, and predictable treatment option for the restoration of fresh postextraction infected sockets when appropriate preoperative procedures are taken to clean and decontaminate the surgical sites," the study authors wrote.

Additionally, the processes the researchers used to achieve consistently successful results will be of interest to those who have implants in their toolkit.

"The combination of debridation, curettage, cleaning with 90% hydrogen peroxide, irradiations with yttrium-scandium-gallium-garnet (Er,Cr:YSGG) laser (Biolase Technology), and chlorhexidine rinses together with guided bone regeneration under antibiotic coverture may guarantee the durability of immediate implants inserted in infected alveoli," they explained.

The study is a departure from many implant studies in that it included less-than-ideal patients. The researchers observed a dearth of evidence describing what cleaning protocol is advisable for infected postextraction sites before placing an implant. In their own study, they compared the success of placing implants in these sites to noninfected ones -- in the same patients. While it limited sample size, the results were not affected by intersubject variability.

During the course of the three-year study, 36 teeth (10 incisors, 10 canines, and 16 premolars) were extracted and 36 titanium implants (Mis Ibérica) were placed after extraction, half of which were at infected sites, the test group. Implants in the control group, or at healthy sites, were placed at the same time as those in the test group. The test group underwent the aforementioned cleaning procedure, however.

All 18 patients were between the ages of 18 and 50, had 26 or more teeth, needed two teeth extracted, had no medical contraindications for implants, had sufficient bone for primarily stability, and sufficient mesiodistal space for immediate implant placement, and a chronic periapical lesion of endodontic or endoperiodontal origin at one of the sites per radiographic and clinical examinations.

One month before surgery, the periodontally compromised teeth of the control group were treated with scaling and root planing. Then the patients were prescribed a 250-mg daily dose of azithromycin for five days, following a 500-mg initial loading dose, in order to end active periodontal infection. Four days before surgery, the patients were prescribed 1.5 g of amoxicillin, receiving three equal doses every eight hours each day over the course of 10 days in total.

The patients received local anesthesia for the extraction and implant procedures in both groups. Afterward, they were prescribed 10 mL of 0.12% chlorhexidine for twice-daily rinses. The second stage of surgery took place three months later, when transfer copings were connected to the implants in both groups and titanium abutments were screwed into the implants. Then, after six weeks, metal-ceramic prostheses replaced the provisional crowns.

For the implants to be considered a success, there had to be no clinically detectable implant mobility at the second stage of surgery or during follow-up evaluations, which took place after 12, 24, and 36 months. Additionally, there had to be no radiographic evidence of peri-implant radiolucency, no infection, and no bone loss greater than 2 mm at these evaluations.

The researchers found that the rates of survival were not statistically different in either group (p = 0.720). While the control group had a 100% success rate after three years, the test group had a similar success rate until the 36-month mark, when one implant failed for a 94.44% success rate. The researchers explained that it was due to poor hygiene that could have been prevented with better patient collaboration.

The results in both groups were positive when several other metrics were considered:

- The width of keratinized mucosa was statistically similar after three years.

- Modified plaque index and modified bleeding index values were similar at each evaluation.

- Probing depth and marginal gingival level scores were consistently statistically similar in both groups (p > 0.05).

- Marginal bone level was similar at each evaluation.

While a recall evaluation schedule beyond three years is desirable, the researchers were confident that, in the hands of a skilled surgeon, "immediate implants may be successfully introduced into debrided infected dentoalveolar sockets under a controlled procedure."