Children with the congenital syndrome caused by the mosquito-borne Zika virus may have multiple missing teeth, according to a study in Brazil published April 23 in Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology.

These are believed to be the first reported cases of oligodontia, which denotes six or more congenital missing teeth, in children who were exposed to the Zika virus (ZIKV) in the womb, the authors wrote.

"The findings of the present study reinforce the importance of oral examination and highlights this new association with ZIKV, indicating a possible role of the virus in odontogenesis," wrote the authors, led by Dr. Carla Cristina Gonçalves da Costa of the primary health care program at the State University of Montes Claros in Minas Gerais, Brazil.

In 2013, the Zika virus made its way to North America, and in 2016, the World Health Organization declared it an international public health emergency. The virus is primarily spread through the Aedes aegypti mosquito. However, it also can be transmitted via sexual, intrauterine, and blood routes. The Zika virus has been linked with birth defects, growth and developmental anomalies as well as some motor neurological conditions in adults.

Currently, there is no local transmission of Zika virus in the continental U.S., and the last cases were in Florida and Texas in 2017, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Though there are no current Zika outbreaks worldwide, India faced a significant one in November 2021.

Congenital missing teeth is important, especially since oligodontia is a marker for more than 120 syndromes, including hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Understanding the characteristics of dental agenesis can serve as a supplementary diagnostic tool that dentists can use in their daily practices.

To characterize oral differences in patients with the congenital syndrome caused by Zika, researchers gathered data on 10 children with the condition from the Association of Mothers of Microcephaly in Brazil. They conducted interviews with the children's parents and collected intraoral exams and x-rays from the children.

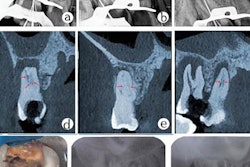

Of the 10 children, two had oligodontia. A 3-year-old boy had 12 congenital missing teeth -- two primary maxillary lateral incisors, two primary mandibular lateral incisors, two primary maxillary canines, one primary mandibular canine, one primary maxillary first molar, two primary mandibular second molars, and two primary maxillary second molars -- according to the study.

The other child, a 5-year-old boy had 15 missing teeth -- four primary central incisors, one primary maxillary lateral incisor right, two primary mandibular lateral incisors, two primary maxillary canines, one primary mandibular canine, one primary mandibular first molar, and four primary seconds molars -- they wrote.

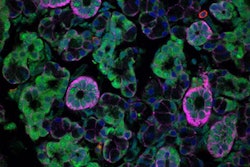

These dental anomalies may be attributed to Zika infecting cephalic neural crest cells, which are embryonic cells that help form craniofacial features, including teeth. Odontogenesis, which starts approximately around the fifth intrauterine week, may be a contributing factor, since Zika infection causes significant comorbidities in fetuses during this period, according to the study.

The study did have a limitation: The children's neurological conditions, specifically their lack of cervical tone, affected x-rays. It resulted in images with artifacts, incomplete images, and a lack of standardization, the authors wrote.

To better understand the occurrence of oligodontia, more reports with different Zika syndrome patients are necessary, Gonçalves da Costa and colleagues wrote.

"The findings of the present study reinforce the importance of oral examination and highlights this new association with ZIKV, indicating a possible role for the virus in aberrant odontogenesis," they wrote.