A team of global researchers used high-resolution imaging to reveal never-before-seen dental details in a 3.67-million-year-old skull of a prehuman ancestor known as Little Foot. The images and insights were published on March 2 in e-Life.

Little Foot, found in South Africa in 1944, is a nearly complete skeleton of an early hominin ancestor that walked upright. The team brought Little Foot's skull from South Africa to the U.K. to scan it with a synchrotron x-ray microcomputed tomography (micro-CT) system from Diamond Light Source.

3D reconstructions of Little Foot's lower left canine revealed new insights about her life. A color map showed that pits in her enamel clearly visible in a close-up scan were less clearly rendered at a further distance.

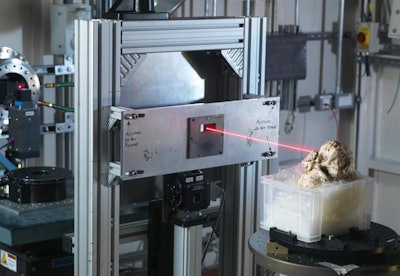

Little Foot's skull being scanned. All images courtesy of Diamond Light Source.

Little Foot's skull being scanned. All images courtesy of Diamond Light Source."These reductions in the normal thickness of enamel correspond to disruptions to the normal growth of enamel and indicate two disruptive events in [Little Foot's] life history," wrote the authors, led by Amélie Beaudet, PhD, from the department of archaeology at the University of Cambridge.

The disruptive events could have been periods of dietary deficiency, nutritional stress, or illness when Little Foot was a child, the authors noted. Interestingly, similar defects were also found in the lower canines of skeletons in the same region.

Beaudet and colleagues also observed less than 1-mm channels in the braincase that were possibly involved in brain thermoregulation. Since Little Foot's time, brain size has increased about threefold, so the information will aid in understanding how brain temperature regulation has evolved.

Additionally, 2D scans of the roots of Little Foot's upper right first molar revealed cementum between dentine and sediments filling the tooth alveolus. The cementum might be a goldmine for researchers to learn more valuable information about Little Foot and her relatives.

A close-up image of Little Foot's skull.

A close-up image of Little Foot's skull."The incremental lines may be used to determine age-at-death as well as specific stress periods that might be related to life-history events (e.g., pregnancies) or disease," the authors wrote.

The imaging device also allowed researchers to observe the vascular canals enclosed in the mandible, which may uncover the biomechanics of how Little Foot ate as well as how her bone was remodeled. Before the advent of synchrotron x-ray CT imaging, the team would have had to cut the fossil into thin slices to learn the same information.

"The fact that the vascular canals could be successfully reconstructed in 3D in the mandible of a 3.67-million-year-old fossil specimen such as 'Little Foot' reveals the invaluable contribution of synchrotron radiation in refining our knowledge of fossil hominin paleobiology at a histological level," the authors wrote.

The paper is the first in a series as more information is being gleaned about Little Foot from the imaging process. The noninvasive technique has implications for the ontogeny, physiology, biomechanics, and biological identity of fossil specimens, according to the study's authors.